Here’s a blast from the past that could illuminate the future of US-North Korean relations.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about how US troops in South Korea might fare after a peace agreement is signed between the US and the Koreas (China, as one of the signatories of the 1953 armistice, would have to be on board too). Some US pundits insist that Kim Jong Un’s goal is to expel US forces from the peninsula, but more sensible observers point to his recent statements that the DPRK might be okay with an American military presence in the south if the state of war was officially over.

But there could also be a more pragmatic aspect to Kim’s feeling about US troops and the Pentagon: their infrequent but not unprecedented role as a restraint on South Korean military forces, especially when conservative, right-wing governments are in control. And one incident in particular, in 2010, shows exactly how the Pentagon’s desire for stability in the balance of forces in Korea has led to forcing restraint on the ROK Army – in this case stopping an artillery attack on a North Korean command outpost responsible for shelling an offshore island and killing two civilians.

I’ve been told by South Korean reporters who follow North Korean diplomacy with the South that this incident has come up in discussions between the two sides, with the message being that the DPRK understands that the Pentagon at times could have a calming influence on South Korean generals anxious to strike back at what they consider provocations. In 2010 it certainly did play that role.

I discovered this act of US intervention quite by accident at the time it happened. This was in 2010, when I was intensely following the escalating tensions between South and North on an hour-by-hour basis. I wrote about it on my blog, Money Doesn’t Talk/It Swears, and then a few years later had the story confirmed by the Secretary of Defense himself, Robert Gates. Here’s my account, which initially ran on January 15, 2014.

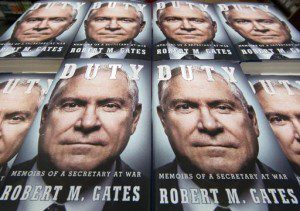

Robert Gates’ new book on his time as Secretary of Defense makes an amazing claim that shows how close we were to war in Korea in 2010. It also describes how the United States stopped the South from launching an air strike at the time.

Robert Gates’ new book on his time as Secretary of Defense makes an amazing claim that shows how close we were to war in Korea in 2010. It also describes how the United States stopped the South from launching an air strike at the time.

Well, I’m not surprised. And I will humbly take credit for being the only reporter to pick up on the U.S. actions, as it happened. My reporting was initially posted on Twitter during the 2010 confrontation between North and South Korea over a disputed maritime border, and later recounted in Salon. The Gates story shows I was right on the money – and, if I can say so myself, quite prescient.

Here’s the story, as reported today by AFP:

South Korea declined to comment Wednesday on revelations that the United States talked it down from launching a retaliatory air strike on North Korea in 2010. The claims were made in the newly published memoir of former US defense secretary Robert Gates.

The 2010 incident followed the North’s surprise shelling of a South Korean border island in November of that year. The attack triggered what Gates labelled a “very dangerous crisis”, with the South Korean government of then-president Lee Myung-Bak initially insisting on a robust military response.

Here’s the interesting part, with key points in bold:

“South Korea’s original plans for retaliation were, we thought, disproportionately aggressive, involving both aircraft and artillery,” Gates wrote in his memoir.

“We were worried the exchanges could escalate dangerously,” he added. Over the next few days, Gates said he, US President Barack Obama and then secretary of state Hillary Clinton had numerous telephone calls with their South Korean counterparts in an effort to calm things down. “Ultimately, South Korea simply returned artillery fire on the location of the North Koreans’ batteries that had started the whole affair,” he said.

Now I didn’t report these exact facts, obviously. But I reported at the time it happened that the Pentagon had basically ordered the South Korean military to stand down. I gleaned this by carefully reading through the lines of an important DoD press conference on the day of the incident. Here’s how I recounted the story last year in Salon in an article about the most recent crisis with the DPRK:

At the height of the crisis, on Dec. 16, 2010, Gen. James Cartwright, the outspoken vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters that he was deeply concerned about the situation escalating out of control. In words designed to be heard in Seoul, he made it clear that the Pentagon wanted to ratchet down the situation. If North Korea “misunderstood” or reacted “in a negative way” by firing back, he said, “that would start potentially a chain reaction of firing and counter-firing. What you don’t want to have happen out of that is for the escalation to be — for us to lose control of the escalation.” Cartwright, and the Pentagon, had no desire to be drawn into a war that was not of their own making.

Few noticed the significance of these words – but I did. Four days later, I tweeted: “When Gen. Cartwright warned of a ‘chain reaction’ that would cause the United States to ‘lose control of the escalation,’ he was talking to SK -not NK.” The morning the military drills were scheduled to restart, many reporters and Korea-watchers on Twitter were predicting that a second Korean War was about to begin. Then, as the time came close for the first live-firing to commence, the South Korean military put out the word that the exercises would be “delayed” because of weather. They were – and then were scrapped altogether. Cartwright’s warning apparently worked. The crisis ended.

Every once in a while it’s nice to know you were were right as a reporter and outdid the rest of the pack. Readers of my blog and Twitter feed know that I’m a big critic of the standard U.S. reporting on North Korea, and I believe my stories from 2010 underscore the validity of that critique. In recent days I had a conversation with a prominent national security reporter who says he was stung by my comments a few years ago on his snarky and totally unprofessional stories on North Korea. Hopefully this post will convince him that I was serious. Snark is not journalism. Ever.